Shape grammars and the Sierpinski triangle

· Reading time: 3 mins

In the last few weeks I've been working on my thesis on procedural content generation and came across the concept of shape grammars in the context of urban and architectural modeling.

Shape grammars at first look like nothing new at all coming from L-systems and rewriting systems in general, but at a closer inspection you come across a fundamental problem: computers can't easily, meaningfully recognize and work with shapes, to the point that there's an entire field of study, computational geometry, dedicated to the task.

Fundamentally, what shape grammars do is move the domain of computation from the symbolic domain (e.g. Markov algorithms and Turing machines) to the visual domain. The Church-Turing thesis suggests, though, that there may be a deep connection between the two domains, which means that there may be a way to reduce the two models to each other.

I came up with the following strategy to implement a simple shape grammar processing system in a little over 50 lines of Javascript.

var ShapeGrammar = function(symbols, prods) {

this.symbols = symbols;

this.prods = prods;

this.state = null;

}

ShapeGrammar.prototype.axiom = function(axiom) {

this.state = [{

sym: axiom,

bound: [0, 0, 1, 1]

}];

return this;

}

ShapeGrammar.prototype.run = function() {

var newState = [], prod;

for(var i = 0; i < this.state.length; i++) {

prod = this.prods[this.state[i].sym];

for(var j = 0; j < prod.length; j++) {

newState.push({

sym: prod[j].sym,

bound: ShapeGrammar.subBound(this.state[i].bound, prod[j].bound)

})

}

}

this.state = newState;

return this;

}

ShapeGrammar.prototype.draw = function(bounds) {

for(var i = 0; i < this.state.length; i++) {

var sym = this.symbols[this.state[i].sym],

points = [], a, b, c;

for(var j = 0; j < sym.points.length; j++) {

a = this.state[i].bound[j % 2];

b = this.state[i].bound[j % 2 + 2] - a;

c = (a + b * sym.points[j]);

points[j] = (j % 2 === 0) ?

bounds.x + c * bounds.width

:

bounds.y + c * bounds.height;

}

sym.draw.call(sym, ctx, points);

}

}

ShapeGrammar.subBound = function(outer, inner) {

return [

outer[0] + (outer[2] - outer[0]) * inner[0],

outer[1] + (outer[3] - outer[1]) * inner[1],

outer[0] + (outer[2] - outer[0]) * inner[2],

outer[1] + (outer[3] - outer[1]) * inner[3]

]

}

The idea is to represent the alphabet as a set of symbols with some added data, and to represent the output of the algorithm not as a string but as a tree, which is feasible without loss of generality (the tree itself is representable as a string). The data added to the symbol is some sort of geometrically meaningful representation of the shape; I chose to represent a shape with a bounding box and a set of points such that . Furthermore, freedom is left to the designer of the grammar to implement a draw method alongside the definition of each shape-symbol; this method will receive a final set of points representing the shape's position at draw time.

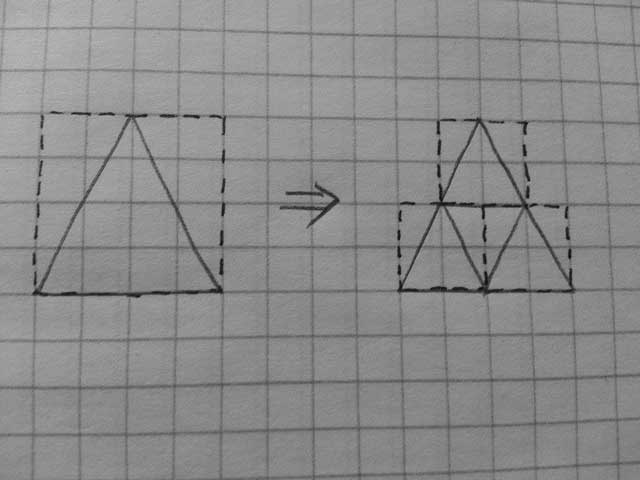

Thus, a typical production rule of the grammar has the following form:

The dashed line represents the bounding box, the full line represents the shape itself. This production is coded by asserting that a certain symbol (e.g. A) represents a shape (the triangle) and by defining the right hand side as a list of A symbols whose bounding box values are defined relative to the bounding box of the left hand side, mapping them over the interval.

In code, that would be

var sierpinski = new ShapeGrammar(

{

'A': {

points: [ 0, 1, 1, 1, .5, 0 ],

draw: function(ctx, points) { /* draw shape */ }

}

},

{

'A': [

{ sym: 'A', bound: [ .25, 0, .75, .5] },

{ sym: 'A', bound: [ 0, .5, .5, 1] },

{ sym: 'A', bound: [ .5, .5, 1, 1] }

]

}

);

At each step, an array of symbols + data (the state) is evaluated by the run() function pretty much the same way L-systems are. The result, of which you can see an example here, is a recursive computation of the Sierpinski triangle.