I built my own business card raytracer in Rust, because why not

· Reading time: 9 mins

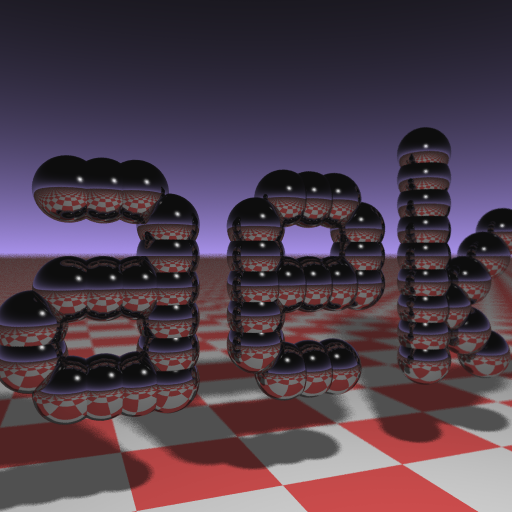

As you may know, and if you're reading this chances are you do, there's this post that's been roaming around for 7 years and periodically resurfaces. It refers to a code golfing challenge dating back in 1984, a few years before I was born. Its rules asked to build a raytracer in C with certain features and functions and shading models. Among those, Andrew Kensler's version, checking in at 1337 bytes, stood out and became world-wide renowned (for good reasons, if you ask me). This was its output.

So, last time I found it on the Hackernews frontpage, I just left it open in a tab for weeks on end. You know, just in case, like one always does. That is, until one fine night the pointless side project fairy visited me in my sleep and whispered in my ear.

The following morning I opened my eyes and knew what I had to do.

I have been wanting to get back into graphics programming for quite a while now, but job duties and personal commitments kept me away from it; besides, as I'm in the process of switching careers, it is high time I polished my professional appearance and got myself a proper business card (by the way, at the time of writing this, I'm still open to offers, nudge nudge, wink wink).

And here it is

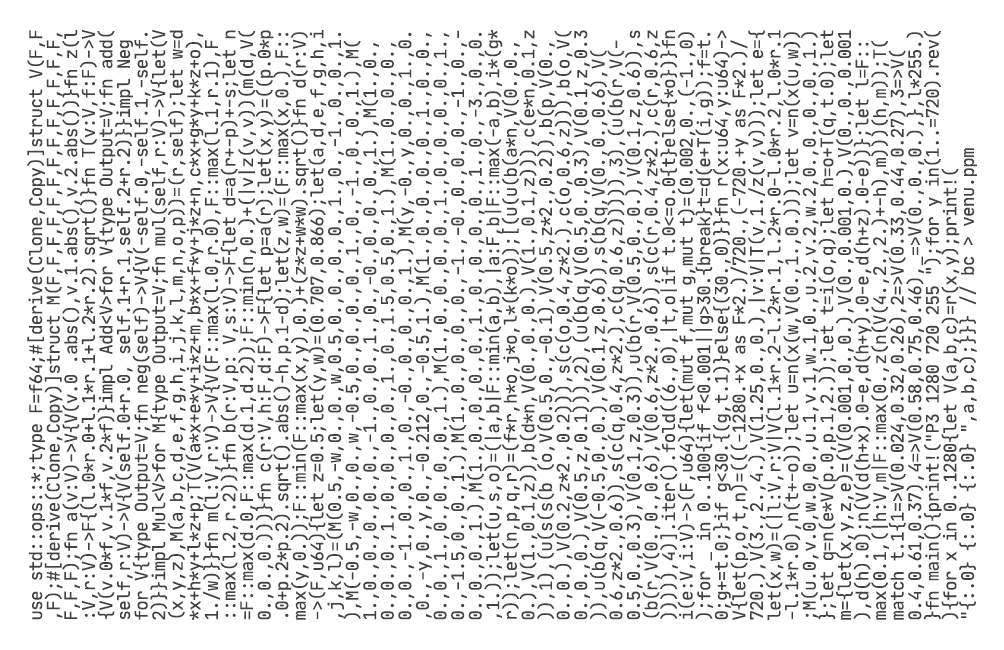

use std::ops::*;type F=f64;#[derive(Clone,Copy)]struct V(F,F

,F);#[derive(Clone,Copy)]struct M(F,F,F,F,F,F,F,F,F,F,F,F,F,

F,F,F);fn a(v:V)->V{V(v.0 .abs(),v.1.abs(),v.2.abs())}fn z(l

:V,r:V)->F{(l.0*r.0+l.1*r.1+l.2*r.2).sqrt()}fn T(v:V,f:F)->V

{V(v.0*f,v.1*f,v.2*f)}impl Add<V>for V{type Output=V;fn add(

self,r:V)->V{V(self.0+r.0, self.1+r.1,self.2+r.2)}}impl Neg

for V{type Output=V;fn neg(self)->V{V(-self.0,-self.1,-self.

2)}}impl Mul<V>for M{type Output=V;fn mul(self,r:V)->V{let(V

(x,y,z),M(a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,j,k,l,m,n,o,p))=(r,self);let w=d

*x+h*y+l*z+p;T(V(a*x+e*y+i*z+m,b*x+f*y+j*z+n,c*x+g*y+k*z+o),

1./w)}}fn m(l:V,r:V)->V{V(F::max(l.0,r.0),F::max(l.1,r.1),F

::max(l.2,r.2))}fn b(r:V,p: V,s:V)->F{let d=a(r+-p)+-s;let n

=F::max(d.0,F::max(d.1,d.2));F::min(n,0.)+(|v|z(v,v))(m(d,V(

0.,0.,0.)))}fn c(r:V,h:F,d:F)->F{let p=a(r);let(x,y)=((p.0*p

.0+p.2*p.2).sqrt().abs()-h,p.1-d);let(z,w)=(F::max(x,0.),F::

max(y,0.));F::min(F::max(x,y),0.)+(z*z+w*w).sqrt()}fn d(r:V)

->(F,u64){let z=0.5;let(y,w)=(0.707,0.866);let(a,d,e,f,g,h,i

,j,k,l)=(M(0.5,-w,0.,0.,w,0.5,0.,0.,0.,0.,1.,0.,-1.,0.,0.,1.

),M(-0.5,-w,0.,0.,w,-0.5,0.,0.,0.,0.,1.,0.,-1.,0.,0.,1.),M(

1.,0.,0.,0.,0.,0.,-1.,0.,0.,1.,0.,-0.,0.,0.,0.,1.),M(1.,0.,

0.,0.,0.,1.,0.,0.,0.,0.,1.,0.,1.5,0.5,0.,1.),M(1.,0.,0.,0.,

0.,0.,-1.,0.,0.,1.,0.,-0.,0.,0.,0.,1.),M(y,-0.,y,0.,0.,1.,0.

,0.,-y,0.,y,0.,-0.212,0.,-0.5,1.),M(1.,0.,0.,0.,0.,1.,0.,0.,

0.,0.,1.,0.,0.,0.,0.,1.),M(1.,0.,0.,0.,0.,1.,0.,0.,0.,0.,1.,

0.,-1.5,0.,0.,1.),M(1.,0.,0.,0.,0.,-1.,-0.,0.,0.,0.,-1.,0.,-

0.,0.,0.,1.),M(1.,0.,0.,0.,0.,1.,0.,0.,0.,0.,1.,0.,-3.,0.,0.

,1.));let(u,s,o)=(|a,b|F::min(a,b),|a:F,b|F::max(-a,b),i*(g*

r));let(n,p,q,r)=(f*r,h*o,j*o,l*(k*o));[(u(u(b(a*n,V(0.,0.,

0.),V(1.,0.1,z)),b(d*n,V(0.,0.,0.),V(1.,0.1,z))),c(e*n,0.1,z

)),1),(u(s(s(b (o,V(0.5,0.,-0.1),V(0.5,z*2.,0.2)),b(p,V(0.,

0.,0.),V(0.2,z*2.,0.2))),s(c(o,0.4,z*2.),c(o,0.6,z))),b(o,V(

0.,0.,0.),V(0.5,z,0.1))),2),(u(b(q,V(0.5,0.,0.3),V(0.1,z,0.3

)),u(b(q,V(-0.5,0.,0.),V(0.1,z,0.6)),s(b(q,V(0.,0.,0.6),V(

0.6,z*2.,0.6)),s(c(q,0.4,z*2.),c(q,0.6,z))))),3),(u(b(r,V(-

0.5,0.,0.3),V(0.1,z,0.3)),u(b(r,V(0.5,0.,0.),V(0.1,z,0.6)),s

(b(r,V(0.,0.,0.6),V(0.6,z*2.,0.6)),s(c(r,0.4,z*2.),c(r,0.6,z

))))),4)].iter().fold((6.,0),|t,o|if t.0<=o.0{t}else{*o})}fn

i(e:V,i:V)->(F,u64){let(mut f,mut g,mut t)=(0.002,0.,(-1.,0)

);for _ in 0..100{if f<0.001||g>30.{break}t=d(e+T(i,g));f=t.

0;g+=t.0;}if g<30.{(g,t.1)}else{(30.,0)}}fn r(x:u64,y:u64)->

V{let(p,o,t,n)=(((-1280.+x as F*2.)/720.,(-720.+y as F*2.)/

720.),V(3.,2.,4.),V(1.25,0.,0.),|v:V|T(v,1./z(v,v)));let e={

let(x,w)=(|l:V,r:V|V(l.1*r.2-l.2*r.1,l.2*r.0-l.0*r.2,l.0*r.1

-l.1*r.0),n(t+-o));let u=n(x(w,V(0.,1.,0.)));let v=n(x(u,w))

;M(u.0,v.0,w.0,0.,u.1,v.1,w.1,0.,u.2,v.2,w.2,0.,0.,0.,0.,1.)

};let q=n(e*V(p.0,p.1,2.));let t=i(o,q);let h=o+T(q,t.0);let

m={let(x,y,z,e)=(V(0.001,0.,0.),V(0.,0.001,0.),V(0.,0.,0.001

),d(h).0);n(V(d(h+x).0-e,d(h+y).0-e,d(h+z).0-e))};let l=F::

max(0.1,(|h:V,m|F::max(0.,z(n(V(4.,2.,2.)+-h),m)))(h,m));T(

match t.1{1=>V(0.024,0.32,0.26),2=>V(0.33,0.44,0.27),3=>V(

0.4,0.61,0.37),4=>V(0.58,0.75,0.46),_=>V(0.,0.,0.),},l*255.)

}fn main(){print!("P3 1280 720 255 ");for y in(1..=720).rev(

){for x in 0..1280{let V(a,b,c)=r(x,y);print!(

"{:.0} {:.0} {:.0} ",a,b,c);}}} // bc > venu.ppm

Granted, it's not as visually fancy as Kensler's version, nor particularly good looking. But it gets the job done, and it has allowed me to experiment on a number of techniques. At 3306 characters, it's also considerably beefier. You can find the full code of my version, but in a much more tolerable shape, here.

The general idea was sourced from this nice ShaderToy which has everything thoroughy explained. I had to of course give the concepts a nice twist. For starters, that's GLSL code: it has, among the others, all the primitives for manipulating vectors and matrices -- a luxury that plain Rust does not offer me. Using external crates sounded a bit like cheating, so I chose not to do that.

Vec3

First thing I did, then, was to reimplement whatever I needed of said algebra functions. This amounts to operations on 3-vectors and 4-matrices used for transformations.

type f = f64;

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug)]

struct Vec3(f, f, f);

impl Vec3 {

fn length(self) -> f {

(self.0 * self.0 + self.1 * self.1 + self.2 * self.2).sqrt()

}

fn abs(self) -> Vec3 {

Vec3(self.0.abs(), self.1.abs(), self.2.abs())

}

fn normal(self) -> Vec3 {

let l = self.length();

Vec3(self.0 / l, self.1 / l, self.2 / l)

}

fn cross(self, rhs: Vec3) -> Vec3 {

Vec3(

self.1 * rhs.2 - self.2 * rhs.1,

self.2 * rhs.0 - self.0 * rhs.2,

self.0 * rhs.1 - self.1 * rhs.0

)

}

fn dot(self, rhs: Vec3) -> f {

(self.0 * rhs.0 + self.1 * rhs.1 + self.2 * rhs.2).sqrt()

}

}

This is a bit verbose, but these operations appear in a lot of places, so gathering them somewhere is bound to save me some space later on. Operations like the dot product could be put in an impl block, where you have to wrangle with the self argument -- yikes! 4 unavoidable characters every single time! A better option, if less idiomatic, is to simply write a regular fn with one-character argument names (nice and comprehensible!). This saves a lot of bytes:

// impl version, more chars

impl Vec3 {

fn dot(self, r: Vec3) -> f {

(self.0 * r.0 + self.1 * r.1 + self.2 * r.2).sqrt()

}

}

v.dot(r)

// fn version, less chars

fn dot(l: Vec3, r: Vec3) -> f {

(l.0 * r.0 + l.1 * r.1 + l.2 * r.2).sqrt()

}

dot(v,r) // same number of chars

Another important thing was deciding what to do with the basic operations. Those are used a huge number of times in the code, but the trait syntax is very verbose; is all of this typing worth it?

impl Add<Vec3> for Vec3 {

type Output = Vec3;

fn add(self, rhs: Vec3) -> Vec3 {

Vec3(self.0 + rhs.0, self.1 + rhs.1, self.2 + rhs.2)

}

}

impl Sub<Vec3> for Vec3 {

type Output = Vec3;

fn sub(self, rhs: Vec3) -> Vec3 {

Vec3(self.0 - rhs.0, self.1 - rhs.1, self.2 - rhs.2)

}

}

impl Mul<f> for Vec3 {

type Output = Vec3;

fn mul(self, rhs: f) -> Vec3 {

Vec3(self.0 * rhs, self.1 * rhs, self.2 * rhs)

}

}

Turns out, it is:

// std::ops traits

let v = a+b*c;

// one-word functions

let v = s(m(b,c),a);

That's around double the characters, and for two simple operations! So paying the cost of implementing operation traits is definitely worth it when they are going to be used that many times.

A small note on this: I ended up saving a bunch of characters by not implementing Sub<Vec3> for Vec3, and going for Neg for Vec3 instead. This saved me from having to type all the arguments out of rhs, at the cost of specifying subtractions as a + -b instead of simply a - b. Again, the cost of an extra + in some places was worth it in the end, as I had relatively fewer subtractions than additions. I wonder: could it be a good idea for the ops trait to have Sub<B: Neg> for A: Add auto-implemented as self + (-rhs)?

Mat4

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug)]

struct Mat4(

f, f, f, f,

f, f, f, f,

f, f, f, f,

f, f, f, f,

);

At first, I implemented a full-fledged linear transform set of operations on Mat4, so that I could build the transformations on the fly. Then I realized I did not really need to do that -- a (note: vectors are actually in but augmented with a 1; it works like that) multiplication function, aptly named something clear and immediate to understand like Z or q or m, would have been more than enough to do whatever I needed to do after actually hardcoding the necessary transformation matrices.

Distance functions

The overall idea of raytracing distance fields is to define some function that can tell me how distant I am from the outer boundary of some object. For example, if I have a sphere of radius 5 located at (0, 0, 10) and cast a ray starting from the origin, the distance will be:

- positive along the ray that goes from

(0, 0, 0)to(0, 0, 5); - exactly zero in

(0, 0, 5); - negative from there to

(0, 0, 15); - zero there;

- and then again positive onwards.

Thus, negative or zero values for a given point means I have hit something. Turns out, a lot of these functions can be represented with closed form vector algebra (check Inigo Quilez's comprehensive list).

From there, for every ray cast, I can pick the closest SDF solid by marching along the ray and stopping as soon as one of the SDFs returns zero or negative distance. Furthermore, I can pair an identifier that represents the object to each SDF function call. This way I can apply different shading rules (a blue sphere, a red box).

A super interesting thing: we aren't limited to primitive shapes, but we can play a lot with Boolean algebra by doing intersections, subtractions and unions, and even more complex stuff. But I was content with the basics, and ended up only needing a box function, a cylinder function and the base Boolean algebra:

fn op_union(a: f, b: f) -> f {

f::min(a, b)

}

fn op_subtraction(src: f, dest: f) -> f {

f::max(-src, dest)

}

fn op_intersection(src: f, dest: f) -> f {

f::max(src, dest)

}

fn sdf_box(ray: Vec3, pos: Vec3, size: Vec3) -> f {

let adj = ray - pos;

let dist_vec = adj.abs() - size;

let max_dist = f::max(dist_vec.0, f::max(dist_vec.1, dist_vec.2));

let box_dist = f::min(max_dist, 0.) + max(dist_vec, Vec3(0., 0., 0.)).length();

box_dist

}

fn sdf_cyl(ray: Vec3, h: f, r: f) -> f {

let p = ray.abs();

let x = (p.0 * p.0 + p.2 * p.2).sqrt().abs() - h;

let y = p.1 - r;

let (cx, cy) = (f::max(x, 0.), f::max(y, 0.));

f::min(f::max(x, y), 0.) + (cx * cx + cy * cy).sqrt()

}

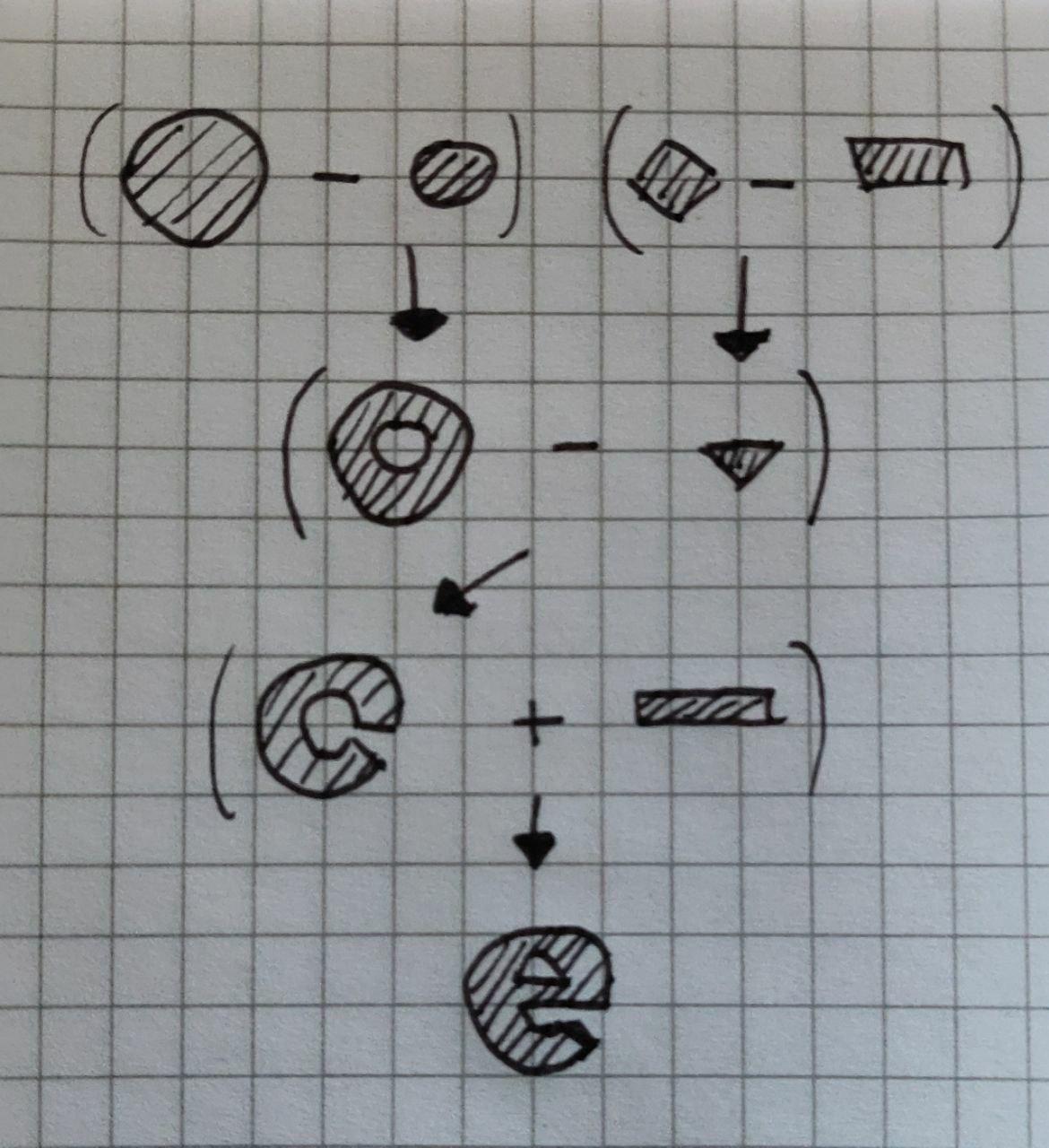

I made the V by intersecting one box rotated counterclockwise, one box rotated clockwise, and one cylinder at the intersection of the two, to make a rounded bottom. The E was reasonably more complex, so I'll let a picture speak in my stead, as drawing that is what I actually needed to do to figure it out in the first place:

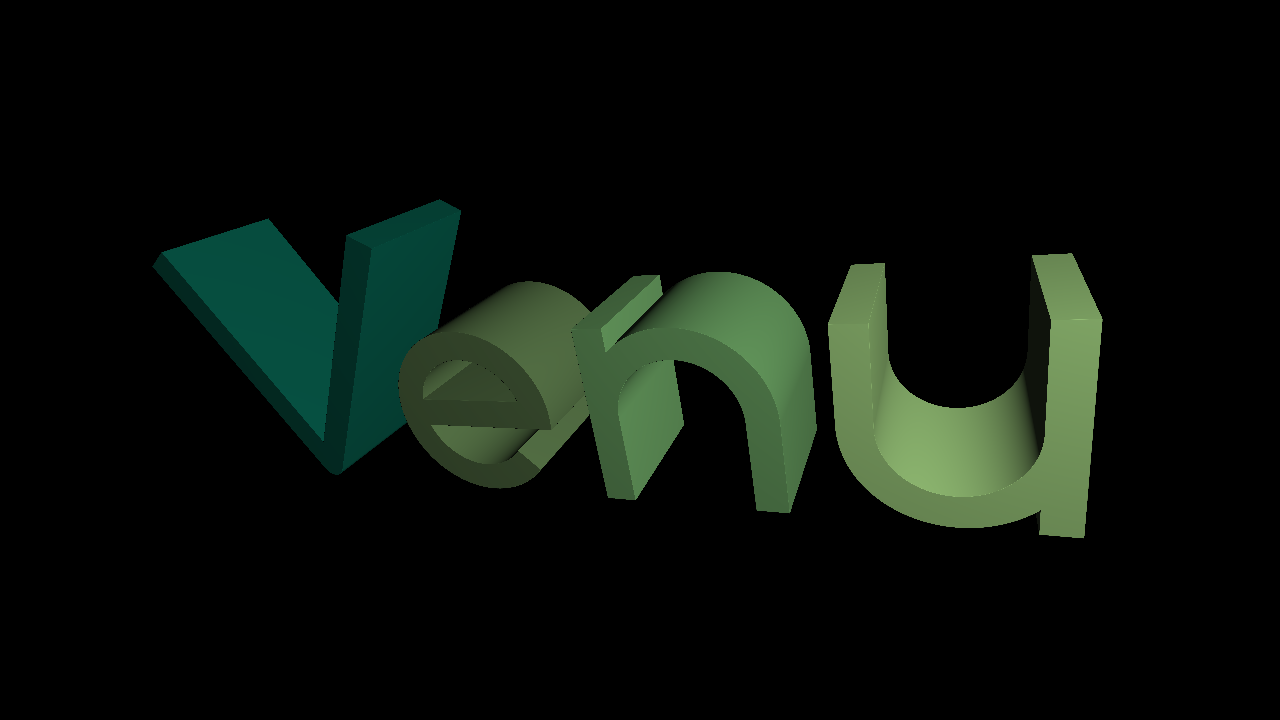

A tall box on the left, a shorter box on the right, and an arc made by subtracting a small cylinder from a larger one, and there you have it: the N, much simpler (I think you can imagine the shapes by now if you scroll up to the rendering). The U was made in the same way but upside down. I've seen better thought-out font designs out there, I must admit, but hey, we all have to start somewhere.

A few more optimizations

Past a couple let statements, it is more convenient to exploit tuple expansion to save space:

let a = 2.;

let b = 3.;

let c = 4.;

// becomes

let(a,b,c) = (2., 3., 4.);

Clearly this is not applicable in places where I need the output of a previous computation, as the result of an expression is not immediately visible in the same expression:

let(a,b,c) = (2., a + 1., b + 1.); // NOPE!

Expanding the tuple also allows to exploit the whitespace next to let. It's not much, but one byte here, one byte there, I overall ended up saving upwards of 2000 characters.

If I had a function used only inside of some other function, but which was too bytes-expensive to inline, I replaced its module-level definition with a closure. For example, I only had to do Boolean algebra in one place, so:

// op_subtraction

fn s(s: f, d: f) -> f {

f::max(-s, d)

}

// becomes

|s,d|f::max(-s,d)

Conclusions

And now for something completely different -- I want to talk about what doing this kind of things feels like. It bears repeating what I said a while ago: writing the super-clean, well indented, well commented, well-architected full stack application with bells, whistles, ironed shirt and firm handshake is a completely different experience from doing this kind of thing. It feels much more like exploratory data analysis, as it is much harder to fully grasp the hierarchy of the code when you're purposefully trying to sacrifice all the best practices you've learned in your career upon the altar of small code. Much more so when you're dabbling in math-heavy techniques such as raytracing, which would benefit greatly from structure and abstractions. I believe my code could be much, much terser than that. But with none of the usual intellectual crutches I rely upon, with the passing of time it felt like any change had harder and harder consequences to predict, and it was harder and harder to evaluate whether I was saving or wasting characters.

At the end of the day, the frustration of not being able to figure stuff out is paid off many times over by the jolt of satisfaction you get when you finally do, and all of that has a constant backdrop of adrenaline from attempting any of the billion ideas you come up with (and can't look up on StackOverflow) to try to solve stuff.

Anyway, I'm dr. Venuta, glad to meet you!

I spent way more time than I think is reasonable on this small piece of code; but then again, I spend way more time than I think is reasonable on videogames as well. And I regret neither:

Time you enjoy wasting is not wasted time

And with strange aeons even time can waste time

-- Abdul Alhazprocrastinated, iirc.